“Village is a place where you can find peace, unity, strength, inspiration and most importantly a natural and beautiful life”

Minahil urfan

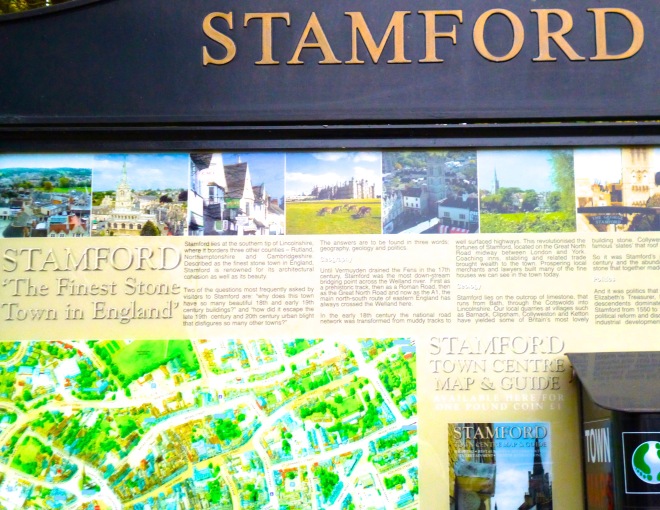

Whether it’s leafy laneways; squirrels on the village green; the local pub; or meandering Bridleways through country estates, British villages have a lot going for them.

We love these quintessential villages, which have long been idealised in word, song and image – and are always a throwback to a less rushed and gentle age.

Obviously, the charms of village life are certainly not unique to Britain.

We’ve had the privilege of visiting villages and small towns in counties such as Italy, Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Slovenia and Switzerland – and found that each has its distinct personality and heartbeat.

But, as the land of our ancestors, Britain naturally holds a special place in our hearts – and we’ve developed a particular fondness for its village life.

Based on our experience, here are some tips for having your very own village experience in England, Scotland or Wales.

Don’t rush it

This is a different type of travel.

The key attraction is the way of life around you – and you can’t truly absorb that if you arrive by coach or car, take a selfie or two, and then rush on to the next stop.

Stay for several days and unwind.

Enjoy the simple things

Waking to the bubbling sound of brooks and streams; enjoying lazy, hazy days; long country walks at sunset; marvelling at the cottages often with thatched roof and wisteria above the door; and discussing life with local residents while raising a glass or two.

This is a priceless lifestyle that is, unfortunately, all too rare in today’s hectic world.

A village experience provides the opportunity of rediscovering these small joys. For the sake of your soul, lap it up.

Do the ‘full English’

This is a traditional breakfast that typically includes bacon, sausages, eggs, tomatoes and a beverage such as coffee or tea.

Depending on your location, it will be called either a ‘fry up’; ‘full English’; ‘full Scottish’ or ‘full Welsh’.

The ‘full English’ is so popular that many pubs offer the meal at any time of day as an ‘all-day breakfast’.

Picnic in the countryside

Village life lends itself to the traditional picnic, rather than barbeques and fast food.

Hotels and cafes will usually help you gather the ingredients for a picnic of sandwiches and wine beneath a spreading tree or even on the village green.

Explore the village headstones

Village graveyards are a fascinating source of social history.

Most adjoin the parish church.

And, in many cases, you need to enter through a wooden archway structure known as a lych or lich gate – the name of which apparently originates from the old English word for corpse.

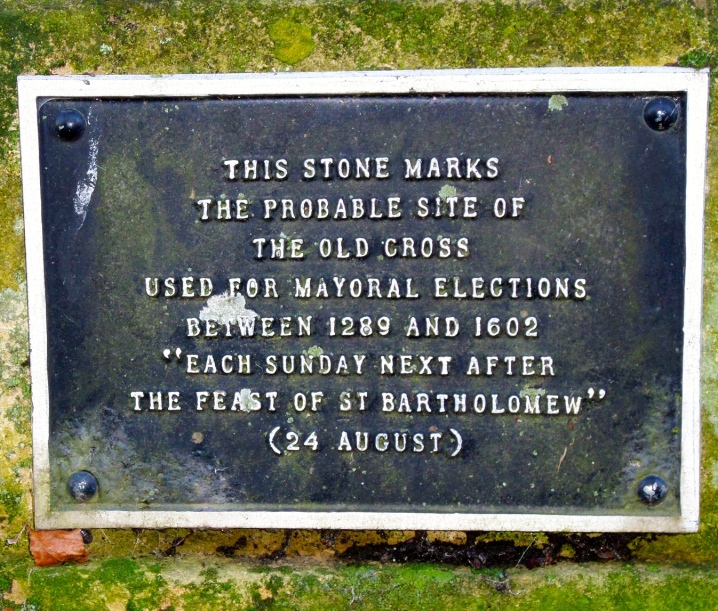

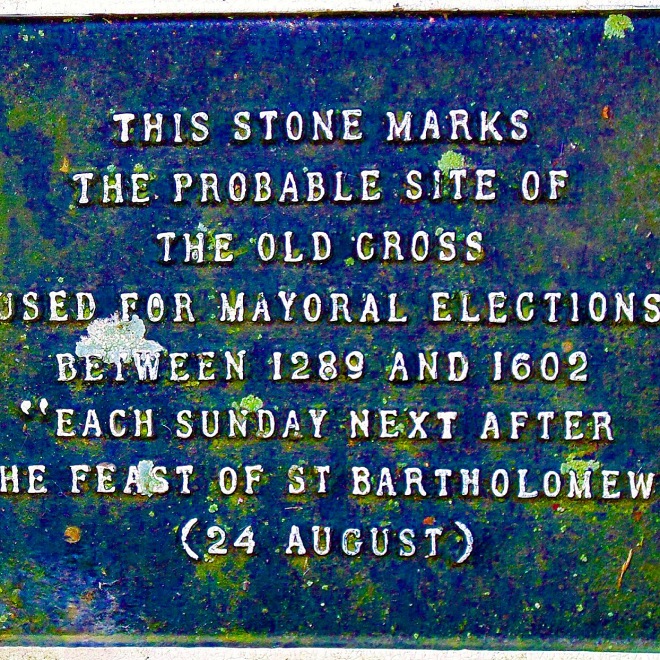

Village graveyards are often the site of old stone crosses – or their remains – sometimes used as preaching areas by roving churchmen or local officials down the years.

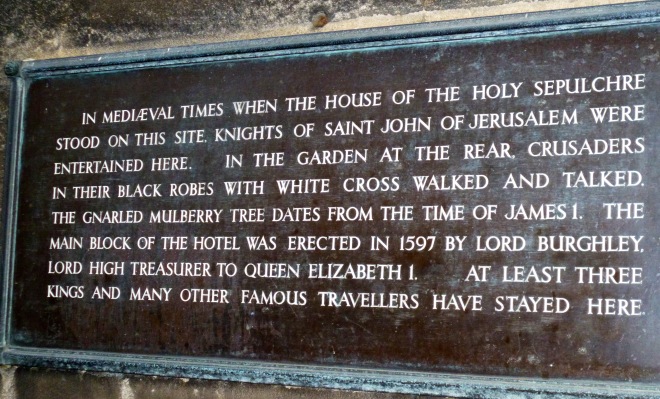

While exploring the old graveyard at Rye in East Sussex, we came across a small plague bearing these astonishing words:

How good is that …..1289!

Another landmark common to most village graveyards is the evergreen yew tree – a symbol of everlasting life.

Visit the church

In many villages, the parish church is one of the oldest, if not the oldest, surviving building.

The scene of a church steeple rising above the surrounding rustic cottages is one of the great iconic images of village England.

If you are particularly keen on local history, most of these churches have fascinating Birth and Funeral Records – and some bear the scars of history, including sword slashes in the stone from wars; historic monuments; and even graves of prominent citizens.

And, of course, the churches are usually a photographer’s dream, with a wide array of designs reflecting the passing parade of life and landscape through the centuries.

Soak up the atmosphere of the pub

“Few things are more pleasant than a village graced with a good church, a good priest and a good pub.”

John Hillaby quotes

Village pubs are wonderful.

We’ve had the pleasure of staying at historical pubs, haunted pubs, canal-side pubs; hotels with literary and sporting links; pubs that have been visited by famous people; and pubs in fantastically scenic, wild and remote locations.

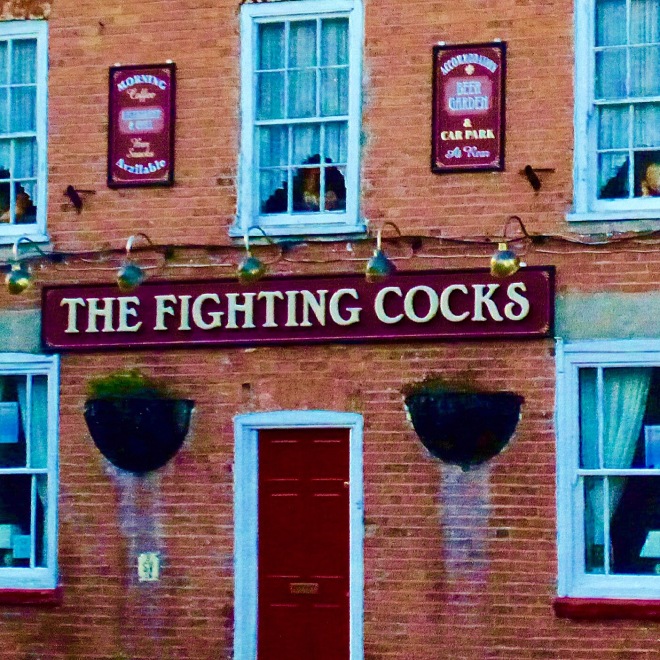

Traditionally, pubs are marked on the outside by a painted sign bearing its name.

In days of old, illustrated signs were essential to identify pubs in an age when most people could not read.

No matter how you look at it, these inns are an historic kind of community centre, where people gather around the bar and tables – these days often accommpanied by their pet dogs.

We’ve seen it well described as a “heady mix of good ale, lager, wine, food and coffee, served with a gentle ebb and flow of conversation”.

Regardless of how you describe it, the pub seems to reflects accurately the spirit of a village. It is a spirit that never fails to make you feel at home.

We consider it an honor to join these people – and truly experience the local culture.

Explore the surrounding countryside

Beyond the charming cottages, past the church and down the road from the pub, English villages are often surrounded by nature’s finest – perhaps rolling hills, lush vales, woods and valleys, dotted with manicured gardens alive with songbirds.

It’s not much of a stretch of the imagination to say that parts of the English countryside are like one big, well-kept garden – especially in Summer.

Narrow laneways, sometimes known as Bridleways, often allow you to move through the rural land – and there may also be walking trails and even canals.

Of course, there are also manors, golf courses and beautiful country homes established over many, many years or owned by those lucky enough to escape the cities.

A village experience is all about discovering, albeit for a short time, the community atmosphere that, too often, has gone missing in today’s fast-paced lifestyle – yet sustains these warm and welcoming villages.

Because, as the pioneering Australian poet, Banjo Patterson, once said: “townsfolk have no time to grow – they have no time to waste”.

Watch for our upcoming article on ‘How to Arrange an English Village Experience’.